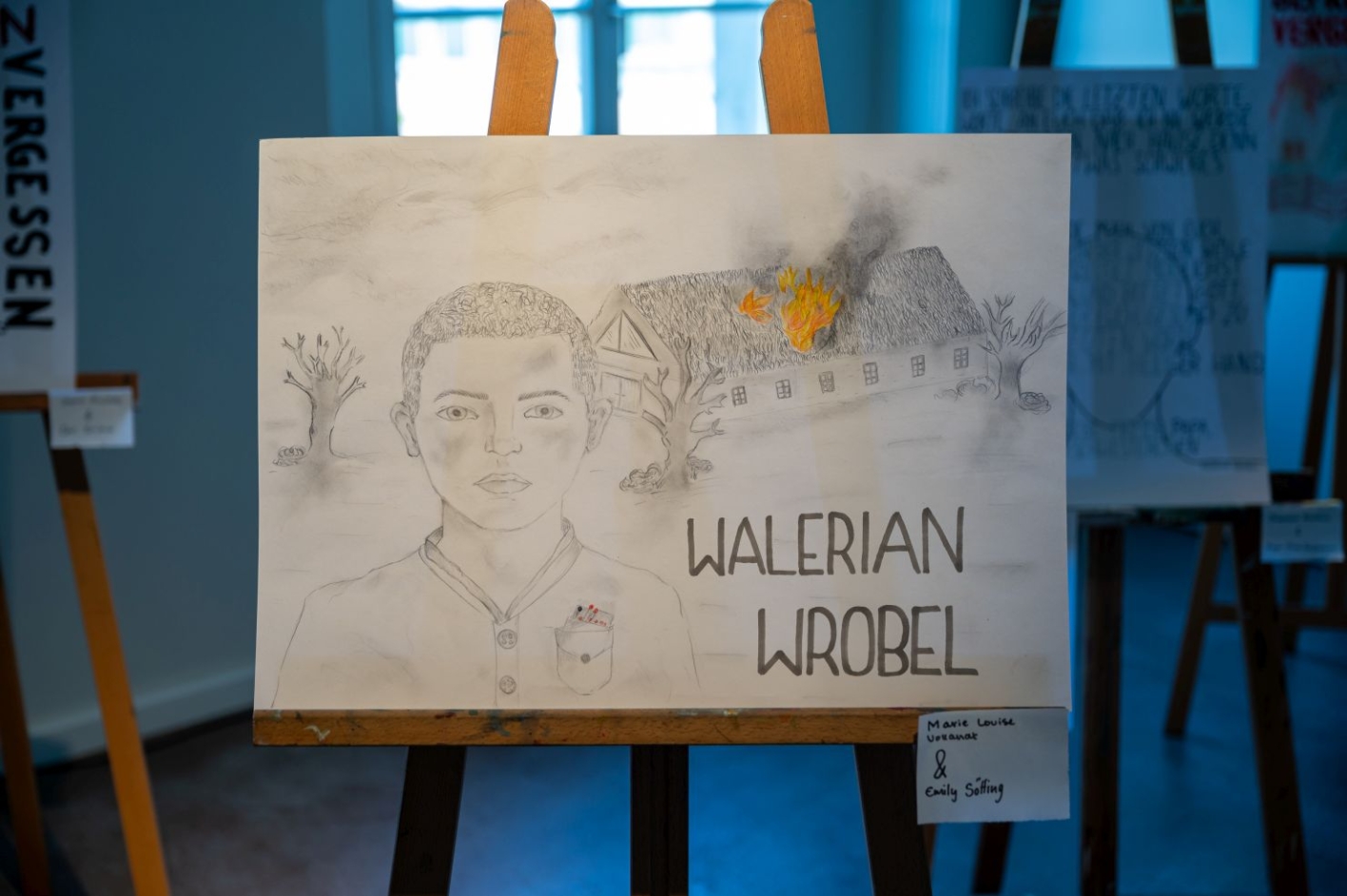

Fałków, 1941. The young Pole Walerian Wróbel is deported from his homeland to a farm near Bremen for forced labor. He stays there for only ten days, has language problems, gets homesick. Suddenly, the barn catches fire. The farmer’s daughter, Luise, has Walerian picked up by the Gestapo. He is taken to Neuengamme concentration camp. On August 25, 1942, Walerian is executed at the age of 17.

Luise was the great-grandmother of photographer Stefan Weger (*1986 in Bremen). He calls his photographic-artistic project on the death of the young forced laborer the “archaeology of an injustice”: he searched for family photos, explored the overgrown area around the old farm, and collected files on the case. The result is a dense visual portrait of a family history under National Socialism that revolves around forgetting and awareness as well as personal responsibility.

Reprint of the artist Stefan Weger's essay from his book “Luise: Archaeology of an Injustice”:

ALONE IN THE ORCHARD

I first met Luise in 1986, shortly after I was born. My great-grandmother was almost 80 years old at that time. When I think back to those few years together, I remember above all the strange aura that surrounded her. Everyone acted differently around her. My grandmother, for example, whom I loved very much, was calm and joyous. But when Luise was around, she became very tense.

While I was at school in Bremen, my history teacher told us the story of Walerian Wróbel. From a pedagogical point of view, it was probably the perfect story to teach us about National Socialist injustice. The story of a teenage boy, whom young people could identify with. A story from the region, making it tangible for the pupils. The whole thing also had a certain topicality, because just a few years earlier, a process of reckoning with this history had begun: a book had been published and a feature film had been made. The lessons practically wrote themselves.

“You know that it was Luise?”

However, what I remember most was not the content of the lessons, but my mother saying: “You know that it was Luise?” At that time, this sentence meant nothing to me. I don’t even know if I understood what she was trying to say. Years, even decades later, this sentence reappears in my head, like an old echo from a deep cave. And now I understand.

I start searching, digging through archives. Here I find the story of a Polish boy who was executed because he was supposed to have set fire to a barn out of homesickness. He had even helped to put it out, because it had probably not been his intention to destroy anything, but to be sent home instead. Walerian Wróbel had only been on the farm for about two weeks at that time, where he served as a “replacement” for the recently deceased farmer, my great-great-grandfather. The fact that my ancestors decided to have the boy arrested by the police, not to protect him but to testify against him, had fatal consequences. Luise, my great-grandmother, provided the decisive testimony. This led Walerian on an odyssey through prisons, court-rooms, and the Neuengamme concentration camp. Walerian Wróbel‘s story ended on the 25th of August 1942 when he was 17 years old in the detention center at Holstenglacis 3 in Hamburg, in what is now the ventilation room. The new

During my research, I find myself on the grounds of the old farm. Alone in the orchard. One becomes so used to having memorial plaques and sites everywhere that a feeling of forlornness creeps over you here. Between the overgrown grass and under bushes, I find bricks from the former masonry. Here are the foundations of the barn that was set on fire. It must have been here where Walerian tried to escape the scene, almost 80 years ago. Over here, buried under leaves and moss, lie old tiles from the kitchen and the walls of the cellar. According to the evidence photos taken by the Gestapo, the matchbox that Walerian supposedly used to start the fire was found here. The very same matchbox that fell out of an old envelope during my first visit to the State Archives of Bremen. History to touch here, history rotting there.

There is a commemorative plaque, of course. Even a memorial sidewalk. But both are several kilometres away from where the farm once stood, which is now an idyllic spot in the Werderland nature reserve. Today, an orchard belonging to a nature conservation association grows over the remains of the farm. As if time and nature win in the end and slowly make you forget.

My journey into the past also takes me to the small village of Fałków, where Walerian was born in 1925. Never have I felt more out of place, even if the woman at the local pizza shop is incredibly friendly. Perhaps this is the feeling that is needed to fight against oblivion. A discomfort that not only creeps up on you when you are at the memorials on the grounds of German concentration camps and being directly confronted with the suffering that your grandparents, great-grandparents or great-great-grandparents inflicted on their fellow human beings. Rather, there is a universal unease that if one‘s own family lived in Nazi Germany, there would likely have been perpetrators or bystanders among them who at least profited from the suffering of others, if not directly contributed to it. Nazi Germany would not have been Nazi Germany if there had been as many resistance fighters as families like to tell themselves.

Discomfort is good. Discomfort does not mean guilt and condemnation. There are hardly any people left who are truly guilty. Discomfort means awareness, understanding and not forgetting. Well-used discomfort leads – in the best case – to dialogue and reconciliation. For me, this project is meant to be a first step in that direction.

Stefan Weger

The editor, portrait and documentary photographer lives and works in Berlin. He studied social sciences, economics and politics in Oldenburg, Växjö and Bremen. In 2021, he graduated from the Ostkreuz School of Photography in Berlin-Weißensee. In his personal long-term projects, he deals with social and political issues through a subjective-documentary approach and research-based photography. The photo book for “Luise: Archaeology of an Injustice” was awarded the German Photo Book Prize in Gold in 2021.

Stefan Weger was as a discussion guest at the FORUM “In Gesellschaft.” on the topic of “Forced Labor as Family History” (from July 13, 2024).