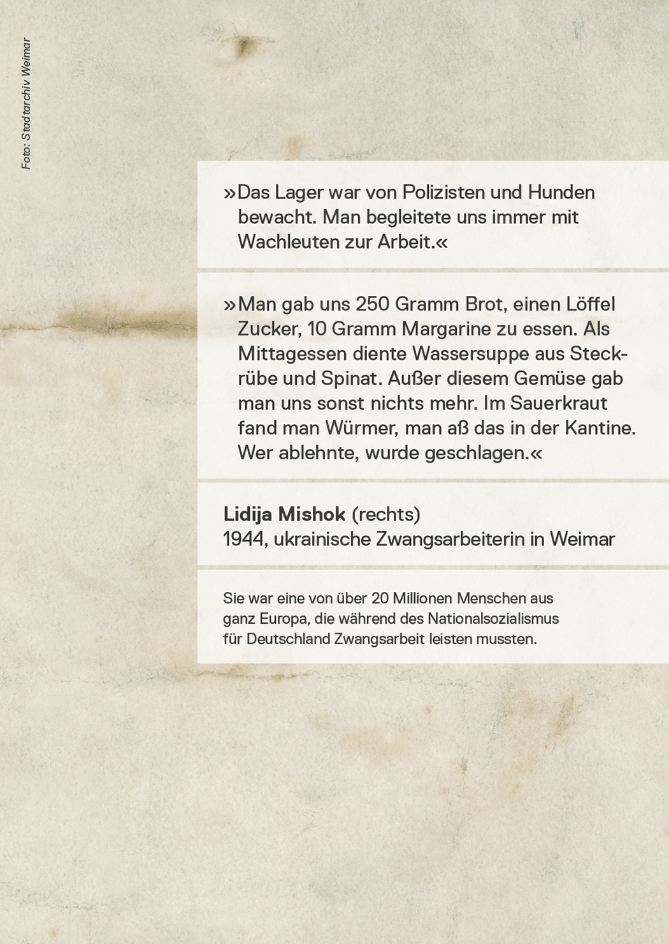

The sixteen-year-old school girl Lidija Mishok arrived at the Fritz Sauckel Factory in Weimar in August 1943 from the Ukraine. An interview that she gave as part of a critical re-examination of forced labor in Weimar gives a sense of how precarious life and work was for her.

Lidija Mishok lived in cramped conditions with hundreds of other people from the occupied Soviet Union in barracks located directly next to the factory. Everyone slept on wooden bunks in rooms with 20 people. Lidija Mishok recalls how “the camp was guarded by police and dogs,” and guards accompanied the laborers to work. “We worked from 7:00 am to 5:00 pm, had one hour free; Saturdays we worked until noon; Sundays we had off,” she described her working routine.

The food rations were inhumane: “We were given 250 grams of bread, a spoon of sugar, 10 grams of margarine. Lunch consisted of a watery soup of turnips and spinach. We were not given anything except these vegetables. There were worms in the Sauerkraut; we ate that in the canteen. Whoever rejected it was beaten.” Lidija Mishok experienced the violence of the German guards in the camp and witnessed the execution of another forced laborer.

In contrast to these experiences, the photograph of Lidija Mishok and two female companions looks idyllic. It demonstrates the will of the young women to represent themselves in a way different from their actual living conditions. However, an additional photograph owned by Lidija Mishok shows dozens of forced laborers from the Soviet Union—men, women, and children—in front of barracks in the camp of the Fritz Sauckel Factory, apparently taken on a work-free Sunday.

She was one of over 20 million people from all over Europe, who had to perform forced labor for Germany under National Socialism.